But one day, Dorothy returned to her grandma's house after school, and her dad was waiting.

"Get in the car. Your grandma's dead. And you're coming home."

Coming home for Dorothy wasn't a good thing. Immediately, her father hired her out as a farmhand. She was fifteen.

At some point, she said it was enough, and she went to work as a gas station attendant. It's where she met Leonard. At age nineteen (1938), she married him.

They worked as farmhands until they could get enough of a savings going to buy their own land. They did, and there were ducks and horses and a bunch of soybeans, according to my mom.

They raised two kids on that farm; three if you include my dad (whom she took in when he was sixteen). But the kids moved away and everyone got older. Leonard got sick. And then Leonard got sicker. And then the farm was sold, and the two found themselves in an apartment down the road from the big city hospital, an hour away from any sort of countryside.

Nine months after Leonard died, I was born.

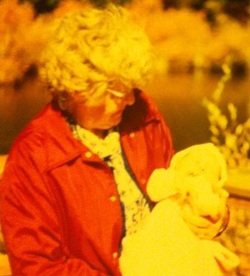

We lived in that apartment, half of my toys and half of my memories in that place. My parents were still young, and they still tried to make ends meet by working a lot. So Grandma and I got close. She was a mother in every sense of the word. And she was a mentor in an even grander scheme.

She got me to start writing books.

This past September, she died after a ten-year battle with dementia. To see her stories fall away one by one, to see her barely remember the farm and her family, it was difficult. It was like none of it had happened and none of it mattered.

And then when the text came in from my aunt (Your grandma's gone, sweetie. I'm so sorry), it felt like there was a void of existence in the world.

It got me thinking, how many stories weren't told ever again. Grandma talked about sitting on the porch, watching her mom work. She talked about a carnival she went to with her sisters and they all took awful photos in the picture booth. She talked about her uncle's kindness, her father's cruelty, her mom's frailty, her older sister's persnickety-ness, and her youngest sister's babyish habits.

Grandma was the last of them to pass. All of those people, all of those stories, are gone.

The question has arisen in my own life and in the lives of those she left behind as to whether or not she continued on after death. A few signs have been shown, a few odd and weird coincidences have surfaced, and not to mention of course the age-old fable of what happened when she actually died. And personally, yes, I do think she's still with us in a new way. I've seen too much to think she isn't. But that point aside, she still lives, because I just shared her story with you and now we're all thinking about her and her life.

That was her worry in life, being forgotten. And now she never will be. Somewhere in the void of the internet, she will sit here on this webpage with a very simplified version of her story told.

That's all books really are; photos taken in a picture booth from the 30's. A thought that passed someone's mind as they sat on the porch watching their mother wash linens. A moment shared between a child and her grandmother in a quiet apartment that will too someday be open to deletion with my death. But it never does get deleted, does it? Because we keep telling the stories. We keep passing them on. I pass her story on, just like she told me the story of her own grandma.

And in that way, no one will ever really die.

Tell your stories. Don't forget them. And maybe we'll all live forever.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed